© 2005, 2006 Paul Berge

A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

“A sense of obligation.”

— Stephen Crane, 1899

“A Man Said To The Universe”

Prologue

(Required reading)

To properly grasp History requires a number two pencil and a sketchpad. That should’ve been included with this book, but if you found it at a flea market or in the Port Authority Bus Terminal, then chances are the sketchpad is gone. That’s OK. It was a sales gimmick, and any old piece of paper will do. In fact, some people just bought the book for the sketchpad, which may explain why you found yours in Port Authority and begs the question: why were you rummaging through trash bins?

There won’t be a test, although you’ll find notes at the end for those reading this for graduate credit. Or you can draw all the images inside your head as mind cartoons. Not mime cartoons; that’d be like Bugs Bunny inside a glass box, and if History has taught us anything, it’s that you can’t keep a bunny in a glass box for long.

Mainly, though, History has taught us that it has little respect for much of anything beyond getting a laugh. Placed in charge of Time, before the beginning of Time, it was assumed by some humans that Clio, The Muse of History, as she came to call herself, would draw things out along a neat line pointing from A to Z, so that anyone along the path, say, in 1480, could note, “Huh, Renaissance,” and conclude, “I must be a Renaissance man.” The term “Renaissance woman,” would not be invented until 1987 so wouldn’t have been in common use in 1480. Although, Savonarola was heard to utter the phrase in 1498 and was promptly burned by an angry, mostly male, Florentine mob. What he actually said was, “Dammit, this is the Renaissance, woman!” No one bothered to ask Clio for a complete reading, so quoted out of context, he was torched. Not that anyone missed the fussy old cleric.

Other muses pitied Clio who was assigned to catalogue the human story while they could dance, sing, and generally skip about in airy robes like randy nuns in Eighteenth Century English gardens. Clio, the plain muse sister, was mostly ignored, never married, but was always called upon to explain who should sit next to whom at family reunions, funerals, and such, and provide all the other muses with a Christmas card list, and—as it always happened—do the mailings herself. The other muses were lazy-assed good-for-nothings. Cute, though.

Humans have a strange relationship with muses. They’ve simultaneously denied their existence, refused to pay them royalties, and yet praised the dancing, frolicking tarts to the point of turning them into a verb: “To muse” means to sit around doing nothing while fantasizing about scantily clad bimbos dancing about with lutes. Universities are full of old musers.

Muse Clio, however, did all the unearthly heavy lifting for the earthbound by taking on the not insignificant task of keeping track of Time. Tougher yet, Clio had to explain this weird tumbling motion of physical entities through nonphysical space to creatures with a brain that’s sealed inside a coconut. Unlike keeping a bunny in a glass box, which accepts light from all directions, the human head has only a few apertures to sample the environment—eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and a few million nerve endings acting like burglar alarms to detect if anyone is trying to avoid using the approved openings.

As a result, humans never get the gist of History, so Clio constantly has to draw them a picture. And drawing Time for a human to comprehend…well, you can run through a lot of number two pencils as you sketch and re-sketch the same characters in what to humans are often mistaken as different settings.

It was Clio who invented de ja vu merely as a training aid for the early French. They didn’t get it, even when Clio broke it down into simple childlike terms:

OK, imagine that this little farm girl, Joan, is a warrior….

L’ jeune fiel? Guerrier? C’est l’impossibilite’! Burn her!

Clio rescued Joan from the French, but left her unattended, only for a moment, and the English burned her simply to show the French that they could. It was then that Clio swore she’d never get involved in affecting human History again, just recording it. It was an oath she’d rarely keep.

Despite, or because of her musing, a lot of people got burnt over Historical misunderstandings throughout the ages, and still humans had trouble grasping Time until, through the use of clocks, calendars, and Post-It Notes, or their generic equivalents, there evolved a basic notion of Time as a sort of moving walkway such as what’s found in many airline terminals—places where Time takes on even nuttier interpretations. These people-conveyor belts tempt passengers, who have no appreciation for Time, to use them in the lame hope that they’ll get them to the gate faster. Inevitably, they slam into reality in the form of two obstructers who aren’t really people, standing side-by-side with suitcases, skis and a baby stroller preventing anyone from passing. Modern humans constantly fall for this trick, the illusion that they can get ahead of Time, much to History’s amusement.

Renaissance man, however, concluded that there was no better place to be than the Renaissance, so why try to beat the clock? Invent it, sure, but no need to overwind it. So, he appeared, rode along for a few decades of dancing, lute strumming, and the proper amount of mating with Renaissance woman in what neither one of them would admit was an attempt to perpetuate the era before a trap door opened and they dropped into what Reginald Frap-Breene called the “Dustbin of History.”

Frap-Breene of Mapleton Road, Westerham, Kent used to collect the trash at nearby Chartwell House, Winston Chruchill’s estate, and while dumping the bins he discovered sheaves of rejected manuscripts from Churchill’s various histories of the world: The Boer War Need Not be Boring or Those Darn Dardanelles, which appears to have been a screenplay treatment pitched to and rejected by Disney. This caused Frap-Breene to remark: “Must be the bloody dustbin of ‘istory,” in a 1989 Ken Burns PBS documentary called The Bloody Dustbin of History. Short-lived, it only aired in Iowa because when Britain’s MI-6 discovered that Frap-Breene was actually a Canadian Double-Time agent and had faked his British accent by mimicking Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins, they told the BBC to pressure PBS to pull the film from distribution, which being PBS and insecure about BBC, it did, although, not before the film became extremely popular in Iowa—where no one fears BBC—and it’s still aired, with interruptions, during membership pledge shows…which no one watches.

The Bloody Dustbin of History was also entered into the 1991 Prince Edward Island Film Festival and received Honorable Mention DocuImport. This so inspired a group of Canadian punk musicians that they named their band The Bloody Dustbins. Tragically, they were all lost in a ferry boat accident in Digby, Nova Scotia when their lead singer and van driver, Stewart Fry—who used the stage name, Stir Fry—drove their GMC van off the boat before it had docked and killed any hopes of the Bloody Dustbins changing music history, which was OK because they weren’t any good, and they, like Frap-Breene, had been faking it in hopes of stardom.

We’re getting a little off the historical walkway, but so you don’t feel bad for the band members you should know that they weren’t drowned. Instead, all their equipment and music were swept away in the current, and, after being fished out of the water, Stir Fry remarked, “This is just stupid, eh,” and he returned to Prince Edward Island to become the curator of the Anne of Green Gables Museum and Waterslide.

History draws lots of fakes and obstructers, but most don’t get unmasked as they ride the moving walkway to some logical dump-off while interacting with various people—like you, perhaps—who rise, dance, and disappear at seemingly unpredictable intervals and—here’s the beauty—accepting it all without going mad, because they, like The Bloody Dustbins, can’t possibly know where their personal trap door might be. Nor do most humans believe that they can see Point Z or define exactly where Point A is, even though they trust that both points exist and therefore stop looking in a vague hope that when they drop through the trap door— “Whoooaaaa!” — all will be made clear.

But History quickly grew bored drawing the human story in neat panels, one succeeding the other, and fairly early on began to doodle, sketching Time in all sorts of looping strips with unusual characters jumping from panel to panel often without any reasonable motivation.

Hey, Peter, Quo Vadis?

Oh, Jesus! You scared me…I, I thought you were, you know…

Dead?

Yeah.

Was, but, you know, resurrected.

Oh, yeah, that…well, you look good.

Feel good. And you? Whither goest thou?

Me? Ah, um…I, ah, goest to Rome.

Rome’s that way, Peter.

Oh…so it is. Silly…thanks.

Glad to be of help.

Well, I should really get goesting, so if I don’t see you again….

No, no don’t hug me. I’ve got tomatoes in my pocket….

Oh, Jesus…Sorry.

Will you look at this shirt, now….

Forgive me. Mea culpa….

Hey, it’s not the end of the world. Not yet. I know a guy in Turin, great at getting stains out...here, you might as well take one with you….

This tinkering with the Timeline—you’re here, you’re gone, ooops, you’re back again—resulted in a cast of bewildered cartoon figures stumbling out of reality through the ages and mucking up the perceived logic of the moving walkway with improbable characters meant to be funny but taken far too seriously. Consider Kaiser Wilhelm II, a popular cartoon figure of the late Nineteenth Century in a comic strip series called Bismarck und Willy ©. Each week, a pugnacious Little Willy would cause all sorts of hijinks in the courts of Europe, upsetting his grandmother, Victoria, and his wimpy cousins Nickie and Georgey. Inevitably, Herr Bismarck would appear, wagging his finger, alluding to Goethe, and Little Willy would learn a lesson about Teutonic honor and then, looking at the dirt, he’d apologize and promise to reform…until next week. It was pleasant; Germans loved it.

Yah, Greta, dis Villy got his kummupance vonce again, yah.

Then, about 1890, History dropped Bismarck from the strip and sketched Kaiser Willy sporting a field marshal’s uniform and a silly helmet with a spike poking out the top. Got to admit, that’s great cartooning, and only History could get away with it. If you or I drew a similar character with a goofy mustache and gaudy uniform, seated on horseback and wearing a silly hat, but instead of a vertical spike we drew, say, an arrow sticking in one ear and out the other, no one would take it seriously. University professors, interrupted in their musings, would sniff, “You’re not serious.” And yet, those very sniffers will write long books about the guy with the vertical spike popping out the top of his hat, speculating how Kaiser Spikehead affected History, when it was History who created the silly figure in the first place and meant it as a gag, for crying-out-loud.

History learned, long before humans began to grasp this concept, that the divide between reality and comedy is all in the placement, vis-à-vis, how things are arranged in space and Time to convince the viewer that what they’re seeing is reasonable. In Kaiser Willy’s case, History simply rotated the old arrow-through-the-hat gag ninety degrees from horizontal to vertical and cartoon became reality. Humans accept it, especially when you use words like “vis-à-vis.” Go ahead, sketch out two Kaisers: One with a vertical head spike, one horizontal. Vertically spiked Willy rules.

“Hail the Emperor! Hail the guy with the spike pointed vertically out of his divine head! Death to the horizontal arrowheads!”

And next thing you know spike-headed armies are rampaging across the French landscape butchering those without any spikes at all. And when all the rampaging has run its natural course, and History once again gets bored, History retires Willy to Holland, spikes disappear entirely from hats, and humans become fascinated, instead, with nasty little cartoon men in brushy mustaches. The French, of course, blame it all on de ja vu.

That’s History—an overwhelming force of metaphysical misalignment with all the Time in the world to lead humans into believing that if a round clock strikes twelve at midnight, then the next hour must certainly be one, followed by two and so forth until the coffee perks, and two slices of Wonder bread pop from the toaster in time for Dad to grab one on the way out the door while pulling on his suit jacket, kissing Donna Reed on the cheek and stepping over the kids and dog to get his Chevrolet onto the Expressway before some other toast-eater in a Plymouth gets there first. That, in a run-on sentence, is 1960 in America, mostly, as presented here by History.

It was supposed to be a funny year, except that everyone in 1960 was afraid. The men in spiked hats and the ones with little mustaches who replaced them had been erased, and a whole new cast of cartoon characters was created. Instead of funny hats History gave them mushroom bombs that were potentially far more amusing than any ten armies of spiked horsemen. But even that gag fell flat, and by the end of 1960, History was dying; Clio was having a tough time finding an audience and convincing anyone to keep reading into 1961.

Faced with more than the end of an era, but possibly the end of Time itself, she drew three unlikely heroes to convince the world that History not only still existed but was also unstoppable in its quest to lead humans onto the moving walkway and then block their paths in the hope that eventually, if you put enough humans in a world full of ideas, someone just might escape the glass box before all the bunnies died.

The first character introduced to enlighten the world was Perry Como. Granted, not a lot of laughs and not a big part of our story, he was drawn to provide a soft musical backdrop for the late 1950s and to make getting onto the walkway toward 1961 worth a try. Como was content being a barber in Pennsylvania, but History tapped him on the shoulder and said, “Sing. Not too loud, though. Sing something soothing.” And he did. One of the problems with humans is they often have their own wants that run contrary to History’s desires. Como was selected because he appeared a bit more pliable than Bing Crosby, History’s first choice. Crosby, however, had told History he was under contract to Paramount and, frankly, would rather play golf, which he did until 1977 when History tapped him in the aorta on the eighteenth green. His last words were, “Good game, boys,” not realizing that the “boys” were really obstructers not about to let him play through. Clio whispered, “Those who choose to ignore me…” And Bing went down. Don’t think Perry Como didn’t take note of that.

Unfortunately, Como might’ve been too soothing, because by December 1960 the moving walkway itself was getting mushy, slipping off its rollers, and losing direction so that people flopped on and off at odd stations and not because they refused to move in the one predetermined direction, but because Time simply became unruly in space, a sign that it was seeking its own level, escaping human constraints. In other times—so to speak—that would’ve led to panic, idol worship, and burning of perceived enemies, but because of all the Como music massaging the human soul it led to the acceptance of coincidence in lieu of questioning why things were.

You’ve got the A-bomb?

Yeah, got it about the same time as France.

What a coincidence; that’s when we got ours.

How do you like it?

Kinda pricey.

The two other people History drew to life sort of backfired. They ignored their creator and skipped all over Time without much regard for a coherent straight-ahead flow, putting History itself at risk of getting lost in Time.

History, by the way, is technically neither male nor female. Clio’s a human notion. We can’t envision authority without genitalia. So, if you want to sketch History as a beefy sort of Burl Ives old man in white robes, flowing beard, and wrap-around shades, that’s OK. But for those of us who prefer the Clio female image you might picture a dazzling, widowed Wilma Flintstone—scantily robed in blue. History, unlike its cartoons, is quite comfortable with its entity, doesn’t need your approval, just your adherence to the system as drawn by itself/herself/himself.

This may explain why History became frustrated with its two other characters when they unwittingly ignored History’s plans. Everything short of drawing spikes into their heads the wrong way was tried to make them pay attention, but these humans were cartoons made of special stuff and had no need for convention.

(to be continued…)

To read ahead before the next segment drops, order your own copy of Muzzy – paperback or e-book – through paulberge.com or directly through Amazon/Kindle.

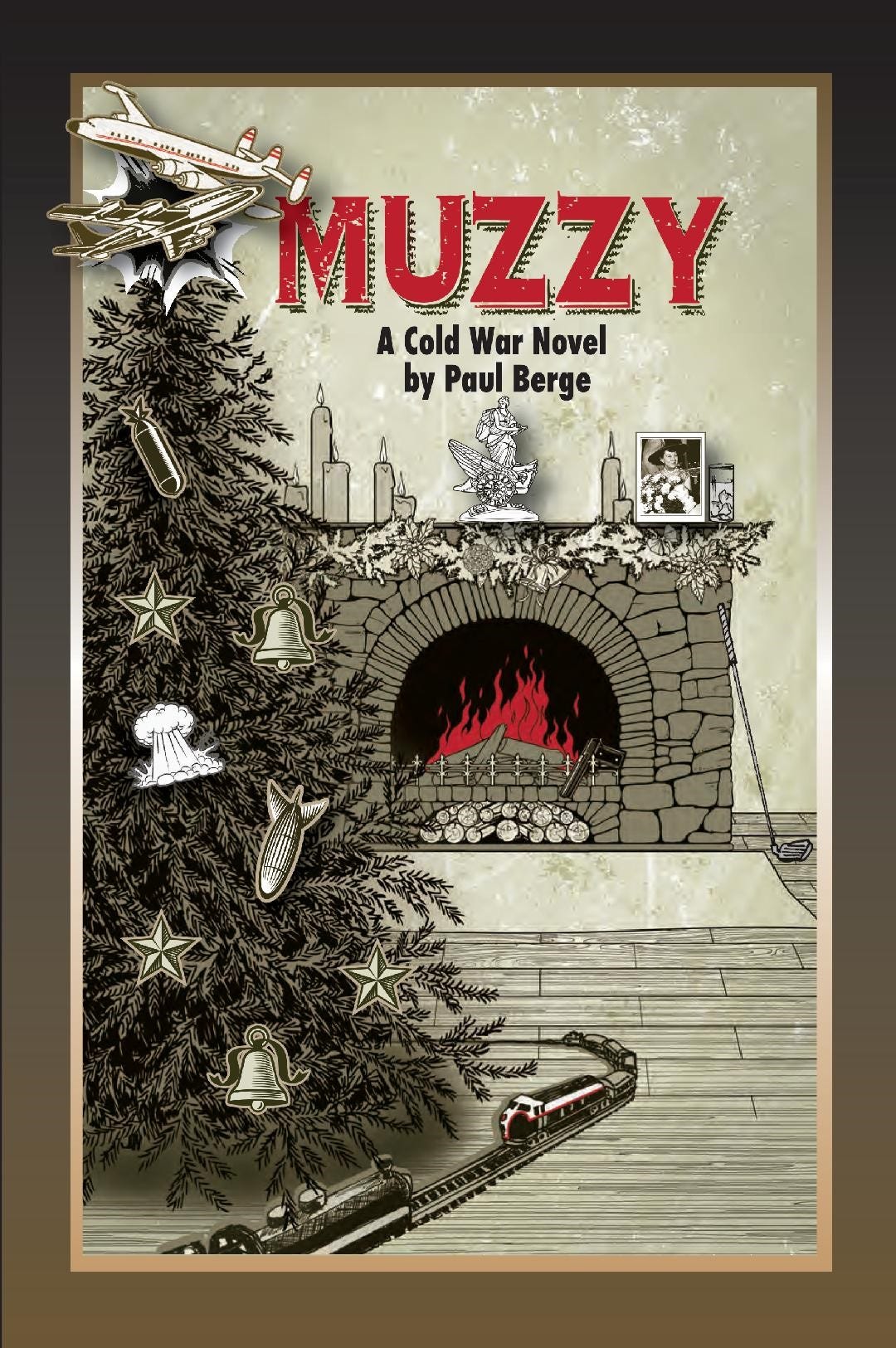

Muzzy was written by Paul Berge and published by Ahquabi House Publishing, LLC; all rights reserved. All wrongs admonished. Cover artwork by Cat Rickers. Layout and editing by Karey Ciel. Cat and Karey are both pilots.

Technical note: those ridiculous spiked helmets were known as pickelhaube…which sounds like a deli side dish.

Pickelhaube on parade with Kaiser Bill